Nick Brandt photographs African animals, aesthetics versus barbarism

To meet Nick Brandt, you need patience first of all, as this photographer is highly demanded and extremely busy, case in point: his latest work – “A shadow falls” – was opening in three European capitals within ten days!

We managed to catch him in Brussels before he left for Paris: patience was rewarded. Nick Brandt is a photographer with a real and genuine passion for his subjects, African animals. His pictures bring this well-known photography genre to another level, adding intimacy and romance. He took his time (and missed his train) to share thoughts with lesphotographes.com on his work and the current condition of African animals.

Do you see “A Shadow falls”, your latest work, as a testament that describes African animals or as a work that should motivate people to protect those animals?

First of all, it’s a last testament. At the same time, those animals are disappearing but that doesn’t mean that we should give up. Like with global warming, anybody with a sense of intelligence knows that global warming is happening and it is getting worse. But that doesn’t mean that we should just give up – we can do things. In the same way, these animals are disappearing really fast and it’s going to get worse but we still have to do a certain amount of things. I’m recording this world as it is now and may never be again. I also want people to help in any way they can and I’m just one part of whatever it may be. It may be environmentalists, it may be photographers… Each of us is trying to inform.

This way of showing animals is different than what we are used to. We tend to think about these photos taken of lions in action for instance, lots of color, and so on. When you first began photographing, did you think about taking pictures as you do portraits in black and white?

No, because I’ve never thought of myself as a wildlife photographer. Even when I was going on holiday as a tourist to Africa, before I started, I had my Pentax 67. I was already shooting in black and white and I always hated 35mm. Right from the very beginning, in my first book, there are a few photos that are from the very first ten rolls I ever shot in Africa; if you look through all my contact sheets, none of it is action. One time, I actually bought a very slight telephoto and I hated it. I tried it for a couple of days and put it away again.

All of your work is shot with a Pentax 67, with a short lens?

Yes.

With this short lens, how do you get close to the models? Is this easily achieved?

No, but it depends – every animal is different and you never know. The difficulty is the number of places that I can get close to animals shrinks because the habitat is being destroyed. All that is left are the parks and then because all the tourists are going to those parks, for me to be alone with an animal becomes harder and harder. I can’t be close to animals when there are other people there because then I’m blocking their view, so it’s antisocial. So, I’ll be sitting all day with lions, waiting to get their photograph and finally at the end of the day, the lions get up and at that moment tourists in a Land Rover come over the hill. And I have to back away because I can’t block their view. I’ve spent all day spending time so the lions are completely relaxed so that when they get up they won’t even notice my team and I… but then that’s it. It becomes harder and harder. I increasingly have to go during low-season, but even then, there is getting to be no off-season. It’s very frustrating.

Do you have any problems with the tourists or tourist guides?

No, it’s anti-social and it would not be fair to them. Somebody could be on their honeymoon, or holiday of a life time and it’s not fair, so even though it drives me crazy, I have to back off.

Over which period of time was “A shadow falls” shot?

Over four years I spent a total of one year to get these photos. 58 photos, 58 seconds for one year of time spent there.

Beyond this year of photographs, there is also the editing and printing and so on. You do this by yourself?

I feel that when you print this yourself, even if it’s on an ink-jet printer, you learn more about what’s wrong with a photo. I like to do it myself. I think that I spend more time saying “oh that’s not good” or “that’s bad grading.”

So you rework in a continuous flow to improve and to get these results we see here?

Yeah.

How do you proceed before reaching the printing step?

I scan the black and white film and I just use software for the sepia.

Coming back to the life of these animals, you said that there is getting to be less and less of them. I read somewhere that you took a trail road eight years after taking the same trail for the first time and that you were surprised to see so many fewer animals. What happened to them?

Basically there is such an incredible population increase in Africa, even though you think of Africa as huge. Unfortunately the best concentration of wild-life is also where an awful lot of the population is, such as in southern Kenya, in northern Tanzania… Just as the population increases with high poverty, you have these animals which are basically free meat: they don’t stand a chance. They’ll just get eaten and everything gets eaten. The lions will just get killed because they’re killing local livestock. So the lions get poisoned and before very long there is nothing left.

I see from your work both pessimistic views and optimistic ones. Do you share this view?

It’s strange because I’m quite surprised when people mention that to me. I’m surprised they get from the photographs a sense that this is all disappearing. There is nothing in my photographs that says this is disappearing. And yet somehow, I don’t understand how or why, people get that impression. I don’t know why it is.

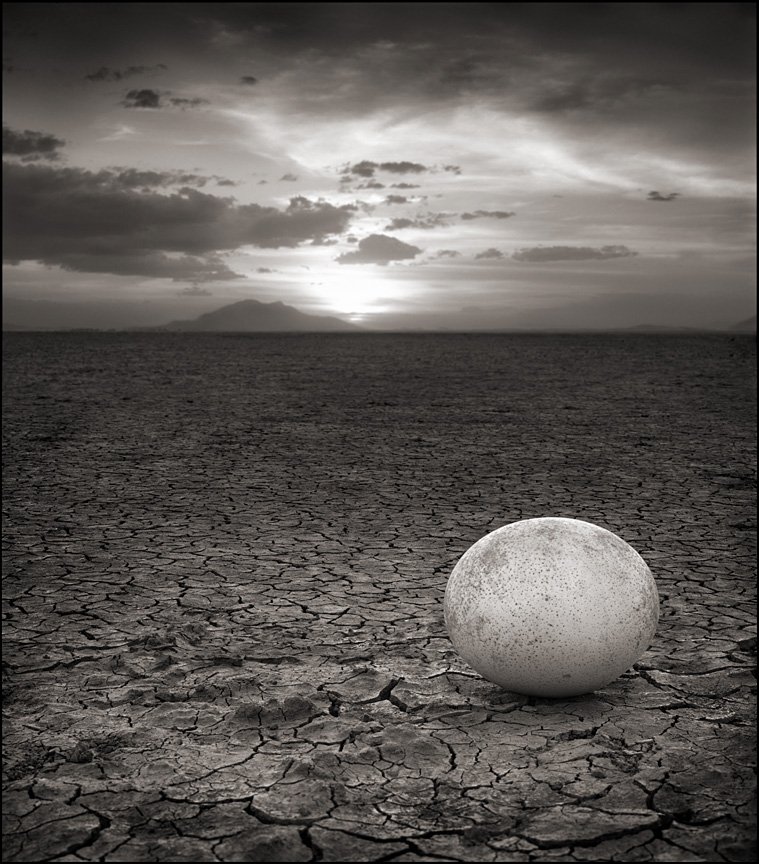

Do you foresee another project after this one?

This book is the second in a trilogy. The first was “On This Earth”, the second book was “A Shadow Falls”, and the third will finish the sentence: On this earth, a shadow falls…. And if you look through ‘a shadow falls’, there is a sequence. It starts in paradise with an abundance of animals, of green, of water. As you turn the pages, it gradually gets dryer and less and less trees, less and less animals, until you get towards the end of the book. The trees are dead and there’s no water left. The final photograph is of the abandoned ostrich egg on the bare lake bed which you can interpret any number of ways. Is there hope in that? Is there despair in that? And I don’t know myself. But it’s just there, left as a question mark that then leads into the third book, which has to somehow – and I’m not sure how – go darker. That will complete the trilogy.

What made you go into the subject of African animals as a photographer?

I’ve always loved animals and as a film maker, I couldn’t find stories meant for adults about animals. Basically, just about every movie with animals is for kids. And I’m not really interested in making a kid’s film although I love the fact that kids respond to my photos, because they are the future generation. And also, film making is completely frustrating and miserable; not when you’re filming, but when trying to get the money. You wait years and years and years, the best years of your life, the most creative years and the years you have the most energy, just not doing anything. Living in California, having meetings with producers, studio people to talk about scripts that never actually get made because you haven’t got the money… The years just go by like that! And it was driving me insane. I couldn’t stand it anymore. I needed to create. As for Africa, I went there in 1995 to direct one of the videos they did for Michael Jackson. And I absolutely fell in love with the place. It was completely magic to me. I had to go back on holiday and that’s when I started taking my Pentax with me. I just realized there is a way of expressing my feelings without the need of somebody else’s money. Initially, it cost a lot. I had to direct stupid car commercials to pay for these expensive trips. I could never have taken these photos the normal way, like most wildlife photographers.

What is your way of working? How do you proceed differently?

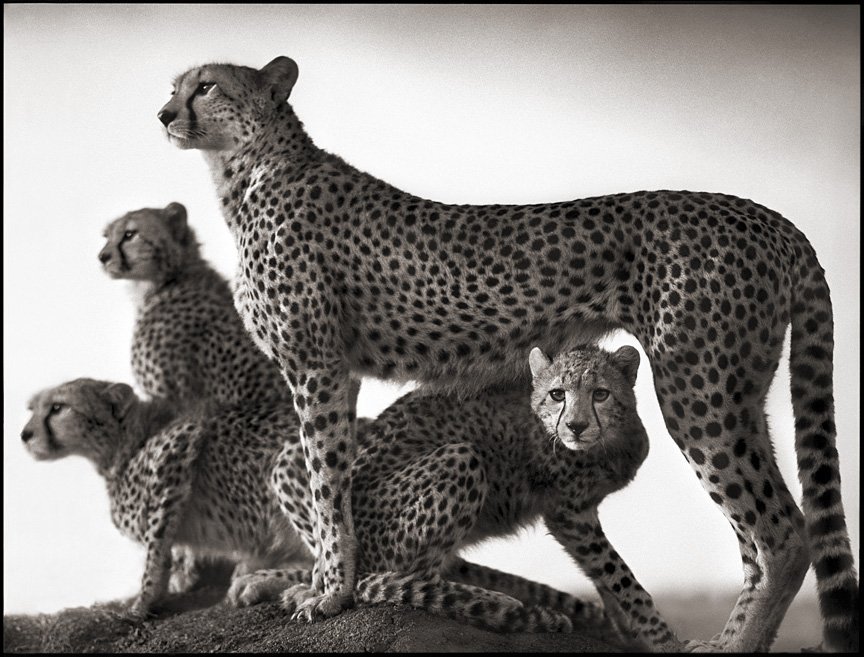

They drive themselves and they spend very little money. I have a team with me with three vehicles with radio to communicate. It’s useful to have the other vehicles there, for example watching the sleeping cheetahs; they can let me know when they wake up. It’s more like doing film. It’s like a shoot with a crew. Another example with the lions: I can spend 17 days in a row going back to that same lion with the wind waiting for it to wake up and on the 18th day it does. I get the opportunities working this way, and I’m using my time more efficiently. But that’s really expensive to do it in such a way.

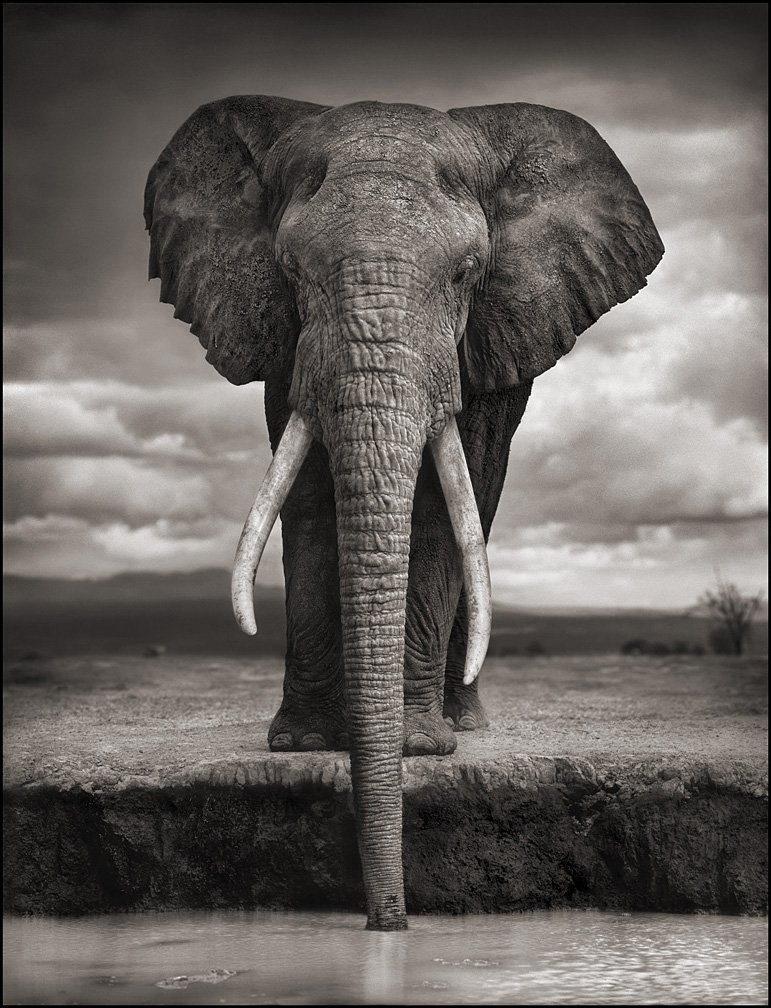

Do you have a certain preference for certain lights with certain animals? For elephants, you usually have a strong sun and clear sky whereas the lions are shot more in dim lights…

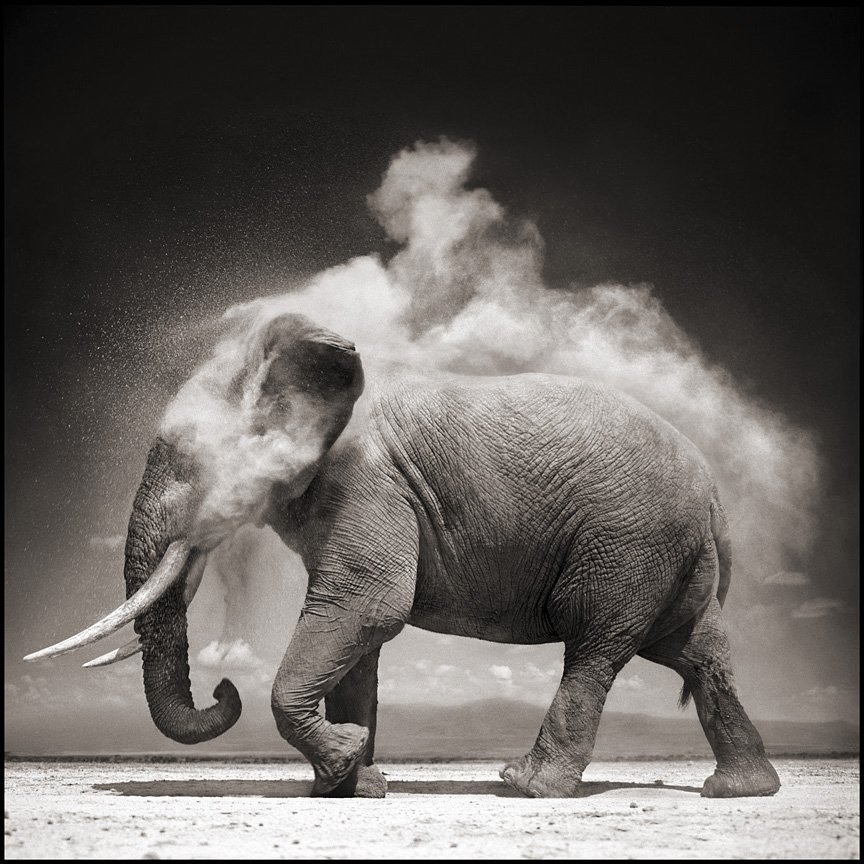

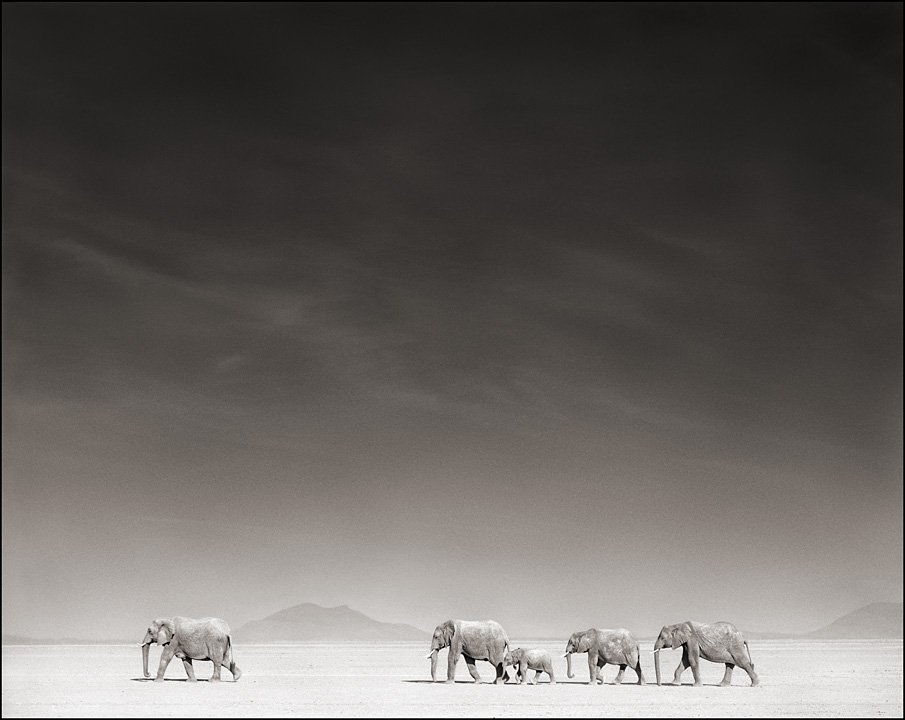

I like shooting in cloud, because I like the softer aesthetic sensibility of that light – the hard light of the sun has too modern a sensibility. Also, cloudy light allows one to see the iconic graphic shape of the animals without sun and shadow complicating the shape. I also find hard sun and blue sky usually very unatmospheric. If you take a look at a lot of my photographs and imagine, instead of the clouds, a clear blue sky, the photograph will be much less interesting. Suddenly there is all this boring empty space with no atmosphere. Now, occasionally, there is a completely clear sky, like with the “Elephant with exploding dust”. But the irony is that the dust is the cloud. With lions, within a couple of hours after sunrise the sun gets too high and then you just can’t see their eyes and it’s just ugly. There is no point in taking a photo and wasting your time. You’ll never see a photograph of mine of lions or cheetahs taken after 8 in the morning, unless it’s cloudy, and then it can be the middle of the day. The gorillas are the same, the chimpanzees are the same. You have to have that cloudy soft light so you see into their eyes. Otherwise you just have black sockets. The elephants are interesting because I love shooting them in clouds because there is, again, that lovely soft charcoal light, but they can also look good in high light because they have these fantastic boney skulls and the way the sun creates contours. Then you can’t photograph them in sun towards the end of the day because then it flattens out all the texture on the contours. So there are a lot of rules I have that mean that I go days and days and days and days without even picking up my camera. I’m just sitting there, going crazy because I’ve come in the rainy season but there is no rain, and there are no clouds, only blue skies.

ow could things evolve towards a better preservation of your endangered photographic subjects?

The best conservation, the most modern thinking conversation is all about working with the local communities that live in the same environment as the animals. That is the only way it can work. The problem is that, even when you do that and even when the local communities understand the importance of the economic benefits that they will gain by having all these tourists coming into looking at these animals, you still only need 100 bad apples with guns and poison to come in from five hundreds miles away, a thousand miles away. With their AK 47, or with their poison, they can just wipe out all that wildlife in a very very very little time. Then, all that work that local communities have been doing is for nothing. And that’s what’s been happening in the last years. Add to that the worst draught in 30 years, the economic crisis so there is a huge drop off in tourism. Then there are Chinese: the new colonialists of Africa. And everything that was so bad about what the Europeans did a century ago, now the Chinese are doing it in a different kind of way, more an economic colonialism. There has been an explosion in demand for ivory from the Far East in the last few years. It’s gone from $400 a kilo in 2004 to $6000 a kilo today. As a result an estimated 10% of the African elephant population – about 30.000 elephants a year – is being wiped out to satisfy that demand. Everywhere the Chinese road construction crews go, the poaching increases. So, if you are a poor African, who earns maybe 100 or 200 dollars a year, it’s hard for you to say no to the money to go kill an elephant for its ivory. They need to feed their family. I don’t blame the local Africans. The persons to blame are the rich First World, or the Chinese, or whatever, the people who want the ivory, or the people who want the gorilla hand to make an ash tray, or whatever the hell it is. Then also, again in spite of all the best efforts, even when an area is protected, you still have people coming in and illegally killing the animals for food, taking down the wood for charcoal for firewood. And that is not just in Africa but everywhere. In Mexico, there is the Biosphere reserve for the monarch butterflies: in the satellite photo in 2004, the mountains are covered in forest and you look at 2008 and it’s gone. And this is in the reserve, it’s not outside. It’s gone. So if everything is getting destroyed even in the reserves, what the hell chance is there… You can keep throwing money in for preservation. For quite a long time I’ve felt very secure that the elephants were going to be ok, that the ivory ban was working, but the incredible fast explosion of the Chinese middle class has changed everything; they don’t give a fuck. They just want the ivory. You have to do it all over again with these Chinese now. Like the Western World slowly learned to treat that world with respect.

Have you planned to have an exhibition in China?

That is a good question! I know that I should because I said “no” to it all because I’m so disgusted by what they do, but at the same time I go “shit, I really should agree because then I can do publicity”. I don’t expect to make that much change with the exhibition. It’s when you do the interviews that go with the exhibition that you try to kind of, what we are talking about now. I should and I haven’t. One of the interesting things, I just started a Facebook page a month ago and I go on online and see which countries people are visiting from. Lots from India, but China: no. And I know I’m making a huge generalization and there are millions and millions and millions and millions of lovely Chinese who would care about animals.

Interview by MF in Brussels on February 21, 2010