LEG interviews ARM: An Ongoing Conversation with Arno Raphael Minkkinen

Since Arno Raphael Minkkinen’s work is of such a corporal nature, I was delighted when I noticed the relationship between each of our initials. This quirky connection makes for a fun title, but doesn’t accurately represent the following interview.

On yet another cold day, this time in Paris, four people met in a café to discuss Arno’s work: Arno, his colleague Kimmo Koskela, RD and myself (Liv Edwards Gudmundson). In this follow-up interview, we spoke of their collaborative film project, of breaking records and of Arno’s recent work in China.

LEG: Last time we ended by speaking about your upcoming film project. Without giving away any secrets, can you discuss how you’ve been using your photographic eye in this cinematic venture?

ARM: Let me share an analogy about the progress on the film: If you drive down Park Avenue in New York from 42nd Street to 86th Street too fast, you hit lots of red lights. If you drive too slow you hit them all. But if you find your speed, you can go really a long time without stopping. So where are we on this film, given that 86th represents actually seeing it? About 44th Street, I’d say.

We have the support of the Finnish Film Foundation to develop a film that is hugely ambitious, so ambitious that maybe we need to make another film first. In any case, the screenplay is in the fourth draft stage. It continues to evolve and become tighter. I write at length, so it was almost a three-hour movie and now it’s down to two-hours. The saga of the story, and its reach, continues to mesh together. Earlier, it was more disparate, now it’s more cohesive. The meaning is starting to emerge.

Writing the screenplay and collaborating with Kimmo is such a wonderful process. We’re both visual people. He is a fantastic filmmaker. He has an eye for approaching things in unusual ways. We want, as everybody does, to create something new in the language of film and narrative. We want a story that pulls you in. It should be in your mind the next morning when you get up, the first thing you want someone to say is: “What did you think?”

The harmony of possibilities in collaboration is such a pleasure, a pleasure that sustains this part of my life, whereas in photography, it’s the discovery of new and different ideas that inspires me.

KK: Maybe the biggest difference is that photography is such an individual work. But in a feature film, you have to call in all the partners and money, which is such a big job that almost all the work is done before you even begin to shoot. I think that is one of the major differences, especially for Arno.

LEG: Will you both see this project through to the end or are you working exclusively on the screenplay?

ARM: One of my roles is the screenwriter, but I am also co-director with Kimmo. As the film moves towards locations and storyboards, then the script is subject to the realities of cost and budget. You’re always looking to improve the story. It gets better as it gets tighter. And that can also save you money in the budget.

In photography I don’t mind telling you that I took a good picture this morning, but with a film it is such new territory. We have to believe that the film is going to be a good one, but we don’t know for sure. We can be certain about our philosophy behind the film however: it going to be 80% fiction and 80% fact. Once you give yourself that kind of carte blanche, you can really move around. And isn’t the past just like that? What happened? Did it really happen? We dream half the time. So, one might ask, what is the 40%? It’s the future: everything that happens next, hopefully this film included.

LEG: What brings you to Paris this time?

Agathe Gaillard. She represents the history of photography in a grand way and I think the history of photography is blessed by her participation in the process of expanding public knowledge and understanding of one of the most remarkable artistic tools we have in the world. And her long dedication to the diversity of expressions that the medium is capable of, rather than narrowing the scope to a particular aesthetic, is also a hallmark of her fame.

LEG: When I heard that you had been traveling to and photographing in China, I was very intrigued. I somehow expected the images to be quite different from your previous work and yet they weren’t. What led you in the direction of China and where were you hoping this new work would lead?

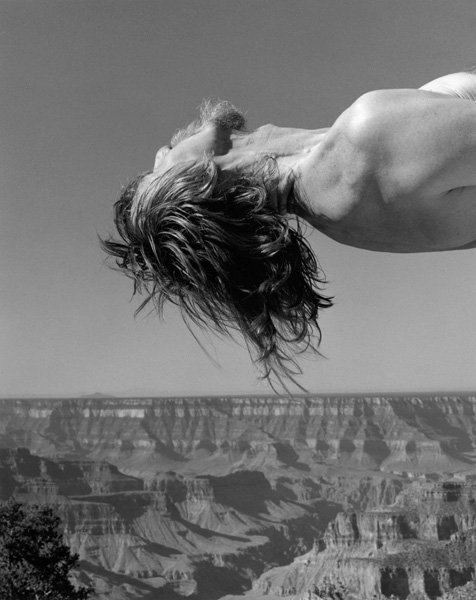

I was invited to the Lianzhou Photography Festival in 2006, about six hours north from Guanzghou (it’s six hours because of the roads, not the distance). But it’s a major city and they invited a number of artists from different parts of the world and gave my wife and I an opportunity to see China. For me especially, it was also the occasion to explore the possibility of taking my work outside of the scope of Finnish farms, Finnish lakes, Parisian rooftops and the American West and start to consider it’s global possibility. If I could fit my way of working into a landscape that was clearly on the other side of the globe, then the work starts to have metaphoric significance as a statement about the world and our relationship to civilization and culture. Not in a profound way, but in more of a visceral way to sense that we are one planet, which is a trite thing to say, but hopefully visualized properly in those gorgeous, rough landscapes. A year later I was invited to do a workshop with a Finnish group on Hainan Island, as far south as you can go in China where you can find palm trees and beaches, but also very rustic jungles.

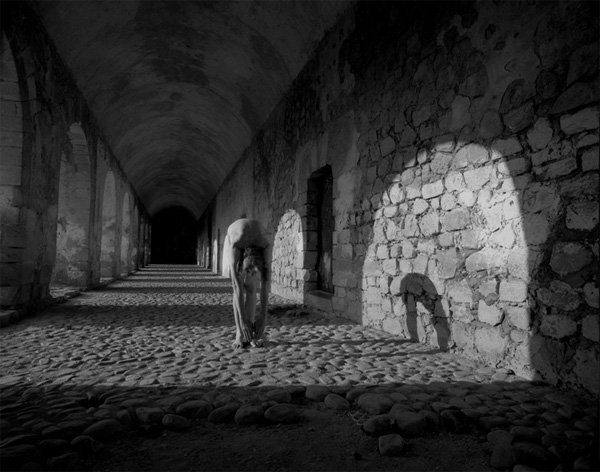

Last summer we were invited to the Dali International Photography Festival in western China, near Burma and Tibet, and I made a lot of work there. I also have a gallery in Beijing, SEE+ Artspace in the 798 Art District, with a growing collector base. So I’ve been producing quite a bit; I have about 30 photographs already from China, many now come with titles. There is one called Awake for the Autopsy, where I’m on a table inside a street vendor’s shop. I motioned to the owner and pointed to my camera showing what I wanted to do. He accepted. I didn’t know it was a calligraphy shop but it made sense with all the things he had around. My body is sticking out into the street like a spoon off a table with the sun coming straight down on me while inside it is all very dark. What the viewer sees is my torso looking really white and very weird. I had one version with my eyes closed.

Along with the China work I’m titling my photographs more and more. I’m having fun with the possibilities. For instance, there was a picture I made two weeks ago called Quarter to Three, Approximately. That was the approximate time I made the picture on the first day of January, as I always try to do the first day of every year. So, in this case, the title comes out of the experience.

LEG: In your images, I often get the impression of a peaceful, oneness with nature. Within this new work, however, there was one image that struck me as almost eerie: Waiting for the Snake… Can you comment on how you select images to show publicly?

The image has to resonate not just with me; it has to resonate with people whom I admire for their insight, judgment, understanding and also for their ability to recognize that even though they may not have seen something before, or that it isn’t necessarily their preferred aesthetic, they can recognize the value.

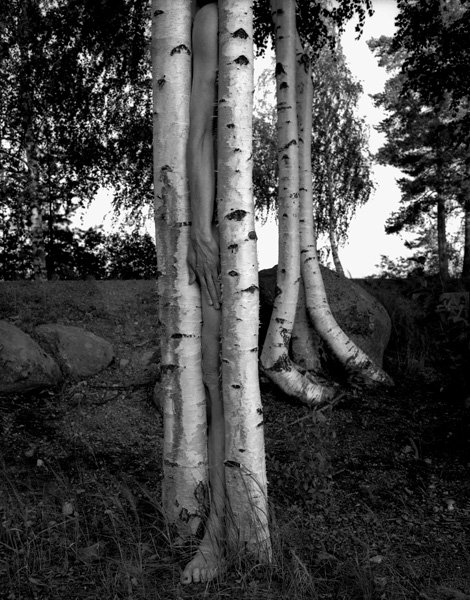

I once showed my work to a documentary photographer when I was younger and he said: “Arno, I don’t know what to tell you. When I go into a forest, I don’t see naked people running in the woods.” And so, I don’t show my work to folks who see life that way because such responses would just make me want to go to bed and put it all away.

I’ve always preferred broad-minded people who can recognize the potential of the medium. I need the confirmation of others to know what is a good picture sometimes. In the case of Waiting for the Snake, I didn’t know how it would turn out. But I did know that the jungle habitat where we were was filled with snakes. I was told this and so my hosts who were in charge of my welfare for the workshop insisted that a doctor with his medicine bag stood next to me. I only made one negative because I didn’t want to extend my luck, but looking around I saw no snakes.

The title comes out of that experience. After printing the photograph, I noticed in the print a flash of light in the water. That was probably the snake!

LEG: In our last interview, we discussed the logistics of some of your photos. Along those lines, how do you select the landscapes and poses?

It’s probably a simultaneous process, meaning that it can’t be just a beautiful view unless I can find something to do within it. To commit myself to a location spot, both beauty and possibility have to concur. I ask myself: how can I do it? What would I do? And, is the background worthy? It has to offer something also allows spontaneity. The best pictures have always involved something that I didn’t imagine beforehand.

LEG: Can you speak about a certain “self-portrait record” that you are in the running for and its personal significance?

I don’t know who first told me this, but at some point I may have the longest running self-portrait in the history of photography. It isn’t that people haven’t photographed themselves over a longer time period than what I will have done once I stop or life stops me, but it’s more about who has exclusively photographed themselves at such great lengths of time. Claude Cahun in that sense still has the record. And there is Lucas Samaras, who began two years before I did. But he went on to do many other things even though he always returned to the self-portrait. Or there is Cindy Sherman who started later than both of us. Still, what I know is that once I started in 1970, my clock never stopped; I’ve never gotten off that bus.

When I start to look at this idea, there isn’t one year where I don’t have a picture that hasn’t been published, collected, purchased, or exhibited. Sometimes there have been years where there was only one image, like the one of my three fingers in 1977, but other years have delivered a dozen keepers or more.

Of course, we live longer lives, so what’s the point, someone might ask, as do I? It’s the stretch of the whole thing, not because of a record, but because of a lifetime. I do want to continue in the same course for the rest of my life, especially now as I’m starting to do writing and film work as well.

LEG: I’ve seen your work exhibited on numerous occasions and each exhibit has it’s own personality. For example, sometimes the contrast in the photos appears different, or the combination of images changes. What role do you play in the exhibition process and to what extent do you influence this way of presenting your work?

If a show is in a museum and it is clear that how it was mounted is viewed as an artistic statement, then I love such opportunities. But generally, I always feel that it’s up to the curator or someone else’s proclivities. I have much more to learn that way. I had the chance to see how Agathe Gaillard put together this new work, more eclectic now than ever before. It ranges from death to sex to birth. There are landscapes and interior spaces, Norway, Finland, China, and France. I wanted to see how she would view these interactions, so I gave her carte blanche.

One photograph needed to be moved. It is titled “Paul Klee’s Chair, Nantes, 2010.” It comes from a wonderful quote by Klee that says: “If you want to understand a painting, you need a chair.” Where it was hung however, the light was too hot. I had printed it soft because there was so much contrast in the subject matter itself. So I am not sure if the bulb was moved away or the picture found another spot.

The hanging all around was terrific. One picture that found a great spot was made in Paltaniemi, Finland, 2009 with my arms out like the wings of a bird. It’s not a very complex picture. But sometimes, if the image idea is poetic and subtle, the picture doesn’t have to be shouting. So that picture doesn’t shout, but it has light and atmosphere. Where Agathe placed this picture, it’s right between the two galleries. One of my arms points to the lower gallery and the other points up the stairs to the higher gallery. It’s like a sign: you can go either way.

LEG : Have you had your photography in any books about portraiture photography?

Yes, there is a new one that just came out. It’s a book by Susan Bright, called “Auto-focus.” It addresses the theme from the perspective of history and contemporary practice. Most of the photographers included are young and most work in color. I’m the old grandpa in it! It mentions my 40 years of work, so I’m happy about that, and yet the genre is so vital and new. It made sense that Thames & Hudson would want to put out this beautiful compilation of self-portrait photography. In the historical section, references are made to Francesca Woodman and John Coplans who began afterwards, yet my work was placed among the contemporary photographers. Well, that’s because I’m alive, of course, but I hope it reflected the idea of being alive with the work as well, especially for me with regard to the 10-year rule idea we spoke about last time.

LEG: You have an interesting outlook on this 10-year rule, first suggested by Szarkowski. Can you explain how your work fits into this approach?

The 10-year rule that Szarkowski shared in a lecture he gave in 1973 struck many of us there as a great challenge. He said we do our best work in a ten-year period of time. The only exception, among folks like Adams, Lange, and Weston, was Atget. The ten-year surge wasn’t something that would necessarily dominate our artistic lives, but at least for me, I took it as a challenge, something to break out of.

I can’t judge my own ten best years, of course, but if I were to try, what sells could be one way to find out where those years fall. When somebody really believes in a photograph enough to buy it, it certainly says something about that image. So when I look at my record, I find purchases from nearly every year that I have been working with equal volumes spread over the whole forty years. The final word on this, of course, doesn’t come from the artist.

RD: Was this morning’s self-portrait your first in Paris?

I’ve made others in the city. But today’s was the first one in Paris this year and my first aerial as well. I have one picture from 1996; it was made on the day they buried André Malraux. The whole of Paris was on the streets moving towards the Pantheon. And I was down by the Seine, under one of those bridges, and it was easy to take your clothes off and make a picture. No one was there to see, except my camera.

Interview by LG & RD on April 17, 2011

Link to Arno Rafael Minkkinen’s website